The evidence comes from cave paintings found in Western Europe, depicting hands with missing or partially amputated digits.

These intentional self-amputations were believed to be performed to seek favor from supernatural entities.

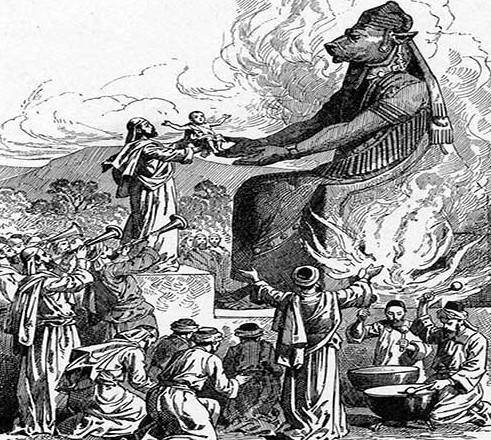

In ancient rituals, sacrificial offerings played a significant role in various cultures throughout history. These ceremonies involved the act of presenting offerings, often in the form of animals, plants, valuable possessions, or even living individuals, to deities or higher powers.

The purpose of these sacrifices was to establish a connection between the mortal and divine realms, seeking blessings, protection, or favor in return.

Sacrificial rituals were deeply ingrained in religious and spiritual practices, reflecting the belief in reciprocity and the exchange of offerings for divine intervention.

A recent study has revealed that our prehistoric ancestors engaged in the practice of cutting off their fingers as part of religious rituals

Archaeologist Professor Mark Collard from Simon Fraser University in Vancouver has presented compelling evidence supporting the theory of deliberate finger amputations in ancient rituals.

The proof lies in the hundreds of cave paintings discovered, which describe hands with missing or partially missing phalanges.

These intricate artworks, dating back 25,000 years in France and Spain, provide a visual record of the practice.

According to Professor Collard, these amputations were not accidental or the result of accidents or injuries but were intentionally performed as part of religious rituals.

The purpose behind these rituals was to elicit help and intervention from supernatural entities. The missing fingers were seen as offerings or sacrifices to establish a connection with the divine.

In these ancient hand paintings, at least one finger was consistently missing from each of the 200 prints.

Some hands only showed the absence of an upper segment, while others displayed the loss of several segments. This uniformity across various cave paintings suggests a deliberate and systematic practice rather than random occurrences.

The group of archaeologist identified around 100 other ancient cultures where finger amputation was practiced, and these societies commemorated their lives through hand paintings and stencils.

This practice was independently developed multiple times across different cultures. They argue that recent hunter-gatherer societies have also engaged in finger amputation, suggesting that the groups in Gargas and other caves could have practiced it as well.

Previously, scientists had put forth various theories to explain the amputations, such as the use of sign language or a counting system.

Some suggested that frostbite or artistic techniques could have led to the depiction of missing fingers in cave paintings.

Collard and McCauley counter these theories by highlighting that finger amputation was not the only form of self-mutilation found in ancient and even some modern societies.

They point to practices like fire-walking, face-piercing with skewers, and using hooks through the skin to drag heavy chains, all serving similar ritualistic purposes.

For example, women of the New Guinea Highlands, continue to amputate their fingers today as a sign of mourning for the death of a loved one.